|

Moving Sidewalks

(Put into service at an airport, 30 January

1958)

Within two years of its first use by

airport passengers, the moving sidewalk caused the death of a tot.

|

Moving Sidewalks

Tot Crushed by Moving Sidewalk at Love Field, Dallas, Texas

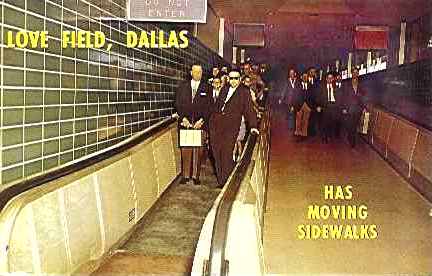

When the moving sidewalk was first opened with the new terminal building at the city's new municipal airport, Love Field, in Dallas, Texas, on 30 January 1958, it was technology being put to use as a modern convenience. Passenger conveyors traveling at the granny-friendly speed of one-and-a-half miles per hour assisted foot traffic for the long walk in each of three concourses from the terminal lobby to the plane ramps. This was the first two-way, moving sidewalk put into service at an airport in America. It was 1,425 feet long and consisted of three loops. Each loop provided a floor-level, rubber carpet, moving continuously between two side-walls that carried a moving handrail of the kind already familiar from its use on escalators. A continuous series of wheeled pallets supported the deck, with flexible connections between them, which were also able to follow vertical or horizontal curves in their track.1

In the 18 Jul 1955 issue

of Time magazine, the cost

was given as $234,704

During the airport terminal building construction, who

should install the moving sidewalks became an issue when an elevator

construction union maintained that their workers should be employed for

that job. A walkout almost halted work when the Dallas building trades

council backed the union.2

As with new technology, there were unforeseen problems in the design. At first these were minor. Several persons had been caught by the sidewalk. Also a dog suffered a broken leg in the mechanism. On 26 Jan 1958, Mrs. R. E. Womack, 38, of Dallas, was sightseeing with her seven-year-old son, Robert Lee Womack. According to Patrolman R. J. Shackelford, in an Associated Press report, the boy was riding the moving seidewalk, and fell near the end of it. The youngster's T-shirt was entangled in the mechanism, and dragged him to the end of the walk. The fingers of his right hand were skinned.

When his mother knelt beside him to help, her own clothes were also

caught up by the belt, and her skirt and petticoat were pulled off. She

was left wearing her knee-length leather coat. The power for the

sidewalk was turned off. The mother went with her frightened son to an

office in the terminal.3

In a later accident, a death resulted. Among the Friday night's crowd of holiday travelers, on 1 January 1960, was tiny, 2-year-old, blond Tina Marie Brandon. She was there with her family for the departure of a relative. Having never seen a moving sidewalk before, she was fascinated by it. Tina ran down the hall to the end of the slowly moving belt. Apparently, she bent down to get a closer look where the it disappeared under the step-off plate. Her coat sleeve was caught by the heavy rubber belt where it turned under at the end, and it continued to drag her clothing into the mechanism. Her left hand, left writst and half of her left forearm were pulled below floor level. She screamed, as did her brother, Wilfred, 5. Before any adult nearby could react, the girl was crushed to death by her own clothing squeezed ever tighter around her body.4,5

After the belt was stopped, E. M. Hardy, a policeman stationed on duty at the terminal said that as he cut off part of her clothes to release her, the material was drawn so tightly around her body, that he could barely insert a knife blade underneath it.

The girl was already dead upon arrival at the hospital, where officials said she had a crushed chest and shoulder. “My child was murdered and there was nothing in the world we could do to help her,” her distraught mother, Mrs. L. C. Brandon told a newspaper reporter. “They have no tools out there at all, not even a crowbar.” The father, L. C. Brandon, the next day said he had talked to a lawyer concerning possible legal action against the city. “I don't want to get anything out of it because of her, but I think something should be done about that machine.”6

The moving sidewalks at the airport remained shut down for investigation. A newspaper account of the accident reported that Dallas Mayor, R. L. Thornton, and two other city officials promised action to prevent further accidents. They were manufacturered by Hewitt-Robins Co. of Passaic, N.J., maker of industrial conveyors and materials handling equipment. Normal clearance between the rubber belt and the step-off plate was less than an inch. Their engineers were expected to make close inspections before any further use of the moving sidewalks.7

The problems associated with safety were already known early in the

development of moving sidewalks in the 1950s. For example, in U.S.

patent 2,782,896, titled “Safety Landing For Moving Sidewalk,” with

application date 1 Jun 1953, the description

began:

“...human nature brings problems in passenger transport by belt conveyor that are unknown to material handling.

For instance, in a recent installation of a ‘moving sidewalk,’ the end guard or landing by which the passengers take off from the belt included a steel plate adjusted so accurately to the curve of the belt that a ‘thin’ pencil lead would roll on the belt against the plate and never bind. Nevertheless, it happened, and frequently, that teenagers' ‘Levis’ caught between the belt and the steel plate. The friction of the rubber on the belt being high and the friction on the steel being low, the cloth of the ‘Levis’ was rapidly pulled in between the steel and the rubber, and worn away. Once the cloth started between the belt and the steel, the progression was fast, and the wearer was caught.

Extended observation showed that the teenagers enjoyed having the belt push them up on the takeoff landing, which often brought heel pressure on the belt as it approached the steeel, and that pressure was enough to distort the rubber of the belt and let the fabric enter between the rubber of the belt and let the fabric enter between the rubber and the steel.”

HISTORY

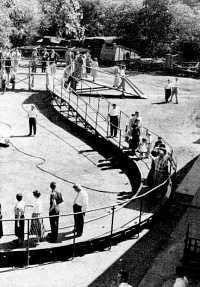

Demonstration in 1955 by Hewitt-Robins, Inc., showing a moving sidewalk able to move around curves. A rubber carpet fastened to wheeled pallets mounted on steel tracks was able to stretch on the outside and contract on the inside at turns.

Imaginative and utopian literature featured moving sidewalks, many

years before their contruction became practical.

The

first moving sidewalk in America was at the Columbian Exposition, the

World's Fair in

Chicago in 1893. According to an article in the Aurora Daily Express, it ran the

nearly the entire length of the 3,500-ft

Great Pier constructed for the use of the people using the fleet of

steamboats that traveled between the exposition and the city, eight

miles away. It was invented by J. S. Silsbee of Chicago, and was

operated by the Columbian Movable Sidewalk Company. The moving floor of

the sidewalk occupied the space

enclosed under a shed-type roof down the center of the pier, with

ticket booths selling 5-cent tickets to ride on it. The passenger would

first

step onto the moving platform, steadied by holding on to one of the

iron posts spaced at intervals

along the moving edge. Each post carried a cautionary sign: “Grasp This

Post in

Stepping On or Off and face FORWARD!”

Once aboard the bare, moving platform which traveled at about two miles an hour, a rider could stand or walk. From this moving sidewalk, a second platform traveled alongside in the same direction onto which the rider could make a low step up to be carried at twice the speed, or to sit on one of its benches. In all, up to about three thousand people could be transported.9 The moving platforms were mounted on railway type wheels on a dumbell-shaped track with a wide loop at each end to change direction, and were electrically powered. It was destroyed in Jan 1894, by a fire in which several other buildings were burned down.

An ambitious installation of a moving sidewalk was made at the Paris

Exposition of 1900, which set a record that still stands for length and

speed of operation. It was 2.1 miles long and connected the principal

points of the exhibition. It was built elevated above the ground level,

with three platforms. The first was stationary, alongside it, the

second moved at 2� miles per hour, and the third moved at 5 miles per

hour. It was capable of transporting up to 14,000 people at a time.

Edison made a movie of it in operation, showing riders standing on it,

and easily stepping on or off.

In America, through the following decades, several grand ideas

were suggested for moving sidewalks in major cities - Washington, New

York and Chicago - but with no outcome. For example, in 1902, there was

reported a “Novel Scheme Backed by New York Millionaires Will Carry

Passengers at Rate of Ten Miles Per Hour” if city officials would grant

permission to “Equip Brooklyn Bridge With Moving Sidewalk.”

Representatives of a consortium of men well-known in the railroad and

financial world (including Cornelius Vanderbilt and Stuyvesant Fish)

were offering to install the moving sidewalks at their own expense and

pay the city $150,000 per year for the priviledge of operating them.

They agreed to limit the charge to not more than one cent per person

per crossing. A consulting engineer drew up plans for four adjacent,

parallel paths, travelling at 2�, 5, 7� and 10 miles per hour. It was

never built.10

However, by 1939, at the New York World's Fair, a 40-foot conveyor successfully maintained a steady flow of the crowds of spectators past the Futurama exhibit. It operated at speeds up to 100 feet per minute.

On 24 May 1954, the first permanent American moving sidewalk was set

rolling at the Erie station of the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad, an

electric line running under the Hudson River between New York City and

New Jersey. It made the trip up the 227-ft incline much easier for

passengers leaving the station, which had been known for years before

as

“Cardiac Alley.” The 5�-ft wide rubber belt traveled over 1,000 steel

rollers, giving a feeling like a foot massage to the people standing on

it. Up to 10,800 persons per hour could be carried on the passenger

conveyor. It was built by the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co., and the

Stephens-Adamson Mfg. Co. It was reported in the UPI newspaper article

that their next project was to be an installation under New York City's

42nd Street to replace the subway train shuttle between Grand Central

Terminal and Times Square.11

On 27 Sep1960,12 the first two pedestrian conveyors in Britain were placed in service along a 16-ft diameter tunnel at the Bank Station on the Waterloo and City Underground line. The Trav-o-lators weres manufactured by the Otis Elevator Co., designed for heavy-duty operation, and together moved up to 24,000 people per hour.

In an article in July 1961, J. P. McElroy estimated fifty as the total number of passenger conveyors in existence at that time.13

An mpeg video of

the

movie made by Edison (9 Aug 1900) clearly showing the twin-speed

platforms of the

moving

sidewalk at the Paris Exposition.

An mpeg video of

the

movie made by Edison (9 Aug 1900) clearly showing the twin-speed

platforms of the

moving

sidewalk at the Paris Exposition.

1 Joseph Nathan Kane, et al., Famous First Facts (6th ed., 2006), 223.

2 AP, '1300 Workers Stage Walkout', The Victoria Advocate (18 Apr 1957), 8. This walkout was mentioned at the foot of a report on a different walkout, continuing on dateline 17 Apr., by Western Electric employees. (source) .

3 AP, 'Boy Hurt in Odd Mishap', Sarasota Herald-Tribune (27 Jan 1958), 8 (source) .

4 UPI, 'Moving Sidewalk Crushes Small Girl to Death', The Times-News (2 Jan 1960), 3 (source) .

5 UPI, 'Tiny Tot Crushed By Moving Sidewalk', Sunday Herald (3 Jan 1960), 4 (source) .

6 UPI, 'Young Girl Dies When Trapped in Moving Sidewalk', The Bonham Daily Favorite (3 Jan 1960), 6 (source) .

7 AP, 'Moving Walk Suspended', Tri-City Herald (3 Jan 1960), 11 (source) .

8 Patent 2,782,896, issued 26 Feb 1957, to Myron A. Kendall and Alfred D. Sinden, Aurora, Ill., assignors to Stephens-Adamson Mfg. Co.

9 Robert Graves, 'The Moving Sidwalk', Aurora Daily Express (26 Jun 1893), 4 (source) .

10 'To Equip Brooklyn Bridge With Moving Sidewalks', The St. Louis Republic (13 Jul 1902), Part 1, 14 (source) .

11 UP, 'Moving Sidewalk Starts Rolling in Jersey City', Sarasota Herald-Tribune (25 May 1954), 3 (source) .

12 Patrick Robinson, The Shell Book of Firsts (1974), 244.

13 J. P. McElroy, 'Pedestrian Conveyors', The Town Planning Review (Jul 1961), 32, No. 2, 125-26.